#something something why pushing nuclear as a solution in france when it's always been dependent on colonial exploitation was a bad idea lol

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In the latest sign of a dramatic deterioration in relations, Niger's military rulers appear increasingly determined to drive France out of any significant sector in their economy - and particularly uranium mining. This week the French state nuclear company Orano announced that the junta - which deposed France's ally, President Mohamed Bazoum, in a coup in July 2023 - had taken operational control of its local mining firm, Somaïr. The company's efforts to resume exports have for months been blocked by the regime and it is being pushed into financial crisis. And the impact could be felt more widely - although Niger accounts for less than 5% of the uranium produced globally, in 2022 it accounted for a quarter of the supply to nuclear power plants across Europe. (...) For French President Emmanuel Macron, already wrestling with political crisis at home, the potential departure of Orano from Niger is certainly awkward in image terms. For it coincides with bruising news from other long-standing African partners - Chad has suddenly announced the ending of a defence agreement with Paris, while Senegal has confirmed its insistence on the eventual closure of the French military base in Dakar. But in any case, the crisis facing Orano in Niger represents a significant practical challenge for French energy supply. With 18 nuclear plants, totalling 56 reactors, which generate almost 65% of its electricity, France has been ahead of the game in containing carbon emissions from the power sector. But the country's own limited production of uranium ended more than 20 years ago. So, over the past decade or so, it has imported almost 90,000 tonnes - a fifth of which has come from Niger. Only Kazakhstan - which accounts for 45% of global output - was a more important source of supply. The continuing paralysis, or the definitive shutdown, of Orano's operations in Niger would certainly force France to look elsewhere. This should be achievable, as alternative supplies can be obtained from countries including Uzbekistan, Australia and Namibia. (...) The French company's predominant role in the uranium sector had for years fuelled resentment among many Nigériens, amidst claims that the French company was buying their uranium on the cheap, despite periodic renegotiations of the export deal. Although the mining operations only started years after independence, they were seen as emblematic of France's ongoing post-colonial influence. (...)

#eli talks#niger#france#pol#something something why pushing nuclear as a solution in france when it's always been dependent on colonial exploitation was a bad idea lol#imperialism

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

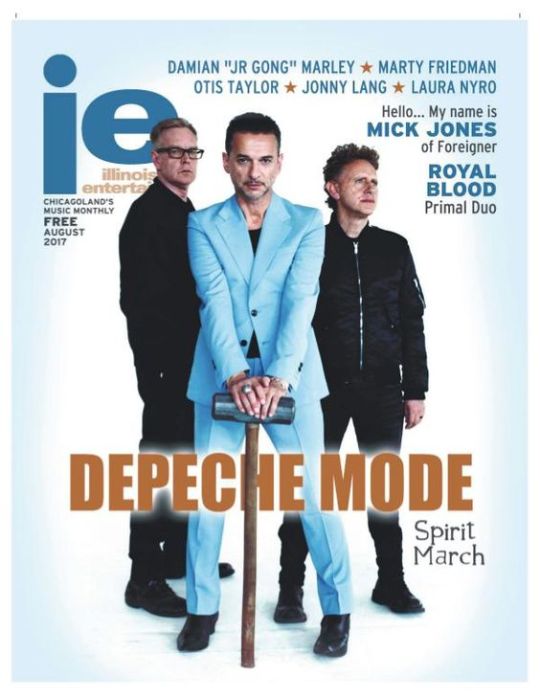

At 56, Depeche Mode bandleader Martin Gore no longer feels the need to pull any lyrical punches. So he gets right to the prickly, political point on the band’s latest Spirit set, starting with its clickety-clacking rhetorical question of a lead single “Where’s the Revolution,” with a grim societal accusation intoned in unusually ominous fashion by frontman Dave Gahan: “You’ve been kept down/ You’ve been pushed ‘round/ You’ve been lied to/ You’ve been fed truths/ Who’s making your decisions?” And the album – in scathing indictments of our corrupt, fossil-fuel-favoring, technology-dependent, extinction-bound culture – just gets angrier from there, in “Fail,” “Scum,” “Poorman,” “The Worst Crime,” and the drone-warfare-damning “Going Backwards,” which posits that “We can track it on a satellite/ See it all in black and white/ Watch men die in real time/ We have nothing inside.”

Gore didn’t set out to pen a set of turbulent protest songs that throb with the dark zeitgeist pulse of our post-Brexit-and-Russian-influenced-Trump-election times. It all arose from an instinctive gut feeling he had two years ago that something had gone wrong with humanity. Something horribly, perhaps irreversibly wrong. When he began composing the Spirit material at the end of 2015, none of these startling global U-turns had happened yet, he recalls. There were serious forebodings, to be sure. “The Syrian crisis was going on, which obviously led to the refugee crisis, the Russians had invaded Crimea, and there was a war going on in the Ukraine,” he sighs, in uncomfortably 20/20 hindsight. “It just seemed like we were getting into bad situations everywhere you looked. And there was that whole spate of police shootings in America – black people getting shot – so maybe I was feeling particularly sensitive or something. But I could feel something in the air that did not feel good.”

Gore also had the unusual vantage point of being a British expatriate who now resides in Santa Barbara, California. Gahan lives in New York, but keyboardist Andy Fletcher has remained in London, where his favorite non-touring activity is going down to his local pub every night and – having been kept up to date on world affairs by the less-biased coverage of BBC News – discussing political frustrations with his good mates. “That’s his thing, and I suppose once you’re a few pints in, those discussions get very lively,” Gore says of his childhood chum, who first formed Composition of Sound with him back in 1980, before adding Gahan (who changed their name to Depeche Mode) and releasing their frothy synth-pop debut Speak & Spell a year later. Whereas in America, he adds, “I do get into discussions with people, but they’re not quite as lively. But I have a 14-month-old and a six-week-old at the moment (with second wife Kerrilee Kaski; he has three kids with first wife Suzanne Boisvert), and the song “Eternal” on the new album I wrote for Johnnie Lee, my 14-month-old daughter, reflecting the EPA and climate change and stuff. And it was kind of serious, but almost meant to be a black comedy, as well, when it mentions the ‘black cloud rising’.” Considering the giant miasma of pollution hovering over China, and the current arms-proliferation posturing of North Korea, he sighs with parental chagrin. “But unfortunately, right now we’re in the middle of that. I mean, I’m not old enough to remember the Cuban missile crisis. But I feel that now we’re in a situation that’s almost as scary as that. Well, scarier because now it’s actually happening.”

When Fletcher first heard his friend’s thought-provoking new compositions, he remembers being somewhat taken aback. Especially considering the fact that Gore traditionally writes on acoustic guitar, which must have made the music sound even more like Dylan-skeletal protest anthems. “At the time, I think me and the producer (multi-instrumentalist James Ford, who also contributed drums on every cut) were a bit worried,” he says. “But then, as we recorded the album, the world situation got worse and worse. We had Brexit. And then Trump actually winning? And then Marine LePen, this hard right-winger, running for election in France, which is not good in a country that is so cosmopolitan? By the time we finished the album, we all thought it was a perfect time to release it. And I’ve always been interested in politics – it’s what I studied at school. So for me, everything that’s happened has been really interesting, and I have to admit that the chatter in the pub has gotten very good because of it.”

Fletcher gets his information from the London Times, the Financial Times, and, of course, the BBC, which he swears by. “The news in Britain is so much better than the news in the States, because you’re really only covering one thing at the moment, and that’s Trump. And all the other things happening in the world? They’re not really covered.” One of the toughest hurdles he ever had to deal with was when Gore relocated to far-off California, and the pair could no longer hang and ruminate on the day’s events, Earth-shattering or otherwise. “It’s weird, because Dave and I sort of connnect as brothers, but – like brothers – you don’t want to be in their company all the time,” he explains of how the Depeche Mode dynamic works. “But Martin is different – he’s been my best friend since age 11, and him moving to America was terrible for me, because it’s difficult, calling someone from London to Santa Barbara, when one person has just woken up and the other’s going to bed.”

What else is in Gore’s livid litany of pet peeves? “Hey – what have you got?” He chuckles. “Trump defunding the EPA and putting a man in charge who doesn’t even believe in climate change? It’s lunacy,” he growls, menacingly. “And unfortunately, he’s not the only one who’s a denier – you find them everywhere you go. And I always say to people, ‘Well, if you don’t believe in climate change, then why don’t we – just for caution’s sake – say that maybe it is happening? What do we have to lose?’” This directly inspired the deceptively gentle Spirit march “The Worst Crime”, which proposes public lynching as penance for ignoring, or harming, the environment (“Once there were solutions/ Now we have no excuses… we are all charged with treason”). “For me, the worst crime is destroying the planet,” Gore declares. “We have this great opportunity to change things, and we’ve had so much evidence, so much scientific proof for so long, but we keep choosing to not do anything about it. And it’s not just destroying the planet for us. It’s destroying it forever. And the system in America is just very, very flawed. I mean, I can’t quite work out when lobbying was a good idea, and why it still exists – and is accepted – I don’t understand, because it’s just so corrupt and so… so wrong. It must happen in other parts of the world, but nowhere near the extent that it does here.”

Even the most sonically-uplifting Spirit number, “Scum,” calls an unspecified antagonist on the carpet for being ‘hollow, shallow, and dead inside.’ Could it be a Wall Street hedge fund manager who bilked the middle class out of millions then walked away, scot free? Gore snickers. “That song is far more powerful if I don’t tell you who my ‘scum’ is,” he elaborates. “Because if I say, ‘It’s this person,’ then it kind of detracts from it, because when a listener hears a song, they put their own imagination to work on it, and then it becomes far more powerful.” But in the “Black Celebration”-ish thrummer “Poorman,” (“Hey, there’s no news/ Poorman’s still has got the blues/ He’s walking around in worn-out shoes/ With nothing to lose,” Gahan murmurs in his classic catacomb-cryptic croon), he demands more accountability. “Again, I think the system is completely screwed and flawed,” Gore says. “People should have gone to jail, but instead they’re getting called into the White House. And the song “Fail” is kind of the synopsis of the whole album, really.” As a species – mistakenly thinking it’s the entitled end product of evolution, “we’re not doing a very good job. We need to start finding the path again.”

Hence the ethereal album title, Gore adds. Some naysayers might describe the record as unequivocally pessimistic, but he respectfully disagrees – pay close attention to what Gahan is singing, and you might fidget uneasily in your seat. “But Spirit is quite realistic – I’m being realistic about what’s going on at the moment, and kind of pointing things out. And by naming it Spirit, I’m hoping that it gets people to think, and maybe somehow rediscover that sense of spirit that we once had, but now seem to have lost.” Mention that DEVO predicted this – humanity’s atavistic de-evolution – four decades ago, and he laughs softly, almost to himself. Everyone’s obsession with their personal device is not only a mass distraction, he believes, but an omen of some kind of impending Apocalypse. “With all of our technological advances and the way we’re using them, it’s, uh, not turning out so well for humankind,” he says. “The only thing that’s headed in the right direction at the moment is medicine. We are getting breakthroughs in medicine, although if we end up in some nuclear holocaust, the medicine’s not going to help us as much. So I think that if we don’t destroy ourselves, we could get to a point where we’re actually able to live for a lot longer.” He pauses to let out a protracted sigh. “But I don’t know what that would actually do for our species, either.”

Fletcher is more optimistic. From an almost scholarly distance, he analyzes England’s recent Brexit snafu, wherein non-London outliers were roiled into enough of a xenophobic frenzy, they essentially voted against their own self-interest to leave the European Union. “The crazy thing is, it was all the villages across Britain – who don’t have any migrants – who voted for Brexit,” he says. “And the fact is, it was a 50/50 vote, and I think any major constitutional change should be more like 60/40, or even 70/30, not 50/50. But I’m not that doom-y about all this stuff. You get stages where things like this happen, so I don’t think the world is any closer to coming to an end.” He has hope, then? “I do, really,” he replies. I mean, what will Trump be able to achieve? Not much through Congress. The only way he can cause a bit of trouble is as Commander in Chief. So yes, this album is pretty angry, but we do normally write about these subjects, but we usually use sex and religion to get the point across. It’s just that Spirit is very direct, although we had one album, Construction Time Again, which was this direct, as well.”

Fletcher also secretly enjoys all of the intrinsic irony involved. Whereas Depeche Mode began as a percolating danceable outfit, it gradually streamlined itself into a sleek, undulating serpent of a synth-rock machine that purred like a long, black hearse leading a funeral procession, aided immensely by Gahan’s ebony-garbed, drone-voiced stage persona. Gore-sculpted songs like “Strangelove,” “Personal Jesus,” “Behind the Wheel,” and “Shake the Disease” straddled the aesthetic line between Goth, New Wave, and industrial, and the band’s diverse audience grew accordingly. And – no matter how grim the trio gets – Fletcher says, “there’s always a lot of people clapping their hands and singing along. And in fact, we got the best reviews we’ve ever had in our career for Spirit, and Depeche Mode generally doesn’t get good reviews. The way our music is made, you need to listen to it a lot of times – you can’t just listen to it twice and then do a review of it. I remember our album Violator – which is a 10 out of 10 record in anyone’s book – just getting average reviews when it came out.

“But we put on good shows, we make good records,” he continues, “And for some weird reason, we’re in our 50s but we seem to be more popular than we ever were. So we’re in a very lucky position – we’ve got loads of our old fans, and they still buy CDs. And then we’re picking up young fans, as well. I mean, we can’t do anything wrong! This American tour sold out faster than our last two tours, and I can’t work out why – I mean, it’s a similar tour, but it’s just gone through the roof. And we’re not a high-profile band – we’re not on the magazines or in newspapers. I just can’t work it out.” And Depeche Mode is one of the few bands from the post-punk era that’s not currently out on an advertised retro tour, playing some vintage cornerstone from its decades-old past, note for note. The group is as relevant – and thought-provoking – as ever these days.

And the three musicians still work well together as a collective. Gahan – who also put out the occasional solo effort – co-wrote four less-political tracks on Spirit, “You Move,” “Cover Me,” “Poison Heart,” and “No More (This Is the Last Time).” “And I used my usual range of analog synths, guitars, and everything came together really fast – we mixed the record on our third session,” Fletcher says, citing Ford’s studio assistance as crucial. But I think technology makes your job harder, not easier, because it gives you hundreds more options. And now there’s this situation with all the superstar DJs,” adds the musician, who still books old-school DJ gigs himself. “In the old days, a promoter would have gotten some young bands to play, but now it’s some superstar DJ who just uses his laptop. And the fact is, it’s replacing bands now – it’s a very unhealthy situation, and for young bands at the moment, it’s just terrible now. Record sales are embarrassingly low, you’re not given any tour support from record companies, so the income available is almost nonexistent. That’s why we no longer get hundreds of great rock bands around the place.”

Gore has yet to see Mike Judge’s hilarious satire Idiocracy, in which Luke Wilson – playing a man of average intelligence from our era – is accidentally frozen in cryogenic slumber for 500 years, during which so many stupid people keep mindlessly breeding that, when he’s awakened in the Great Landfill Collapse – he’s the smartest man in the world. The director’s vision for the future is as grimly dystopian as Gore’s on Spirit, save the public execution “Worst Crime” part. But he has one thing to thank for the album’s relevance, which increases every scandal-beset day. “The American electoral process is so long, the beginning of it had only just started when I began writing this record,” he says. “And it just takes soooo long over here, doesn’t it? It gets so long and dragged out that everyone’s just completely bored with it by the end.” It gave the dirges time to grow, take on even creepier, bigger metaphorical meaning. Or, as Fletcher succinctly puts it, “it’s not like every one of our albums is like this. But I think it’s good that a band like Depeche Mode does a record like Spirit. And people can’t say that we’re jumping on a bandwagon, because, Hey – the songs were written two years ago!”

– By Tom Lanham

Appearing 8/30 at Hollywood Casino Amphitheater, Tinley Park.

55 notes

·

View notes